Returns

The Whale Shark Fishermen

The hunters who switched sides

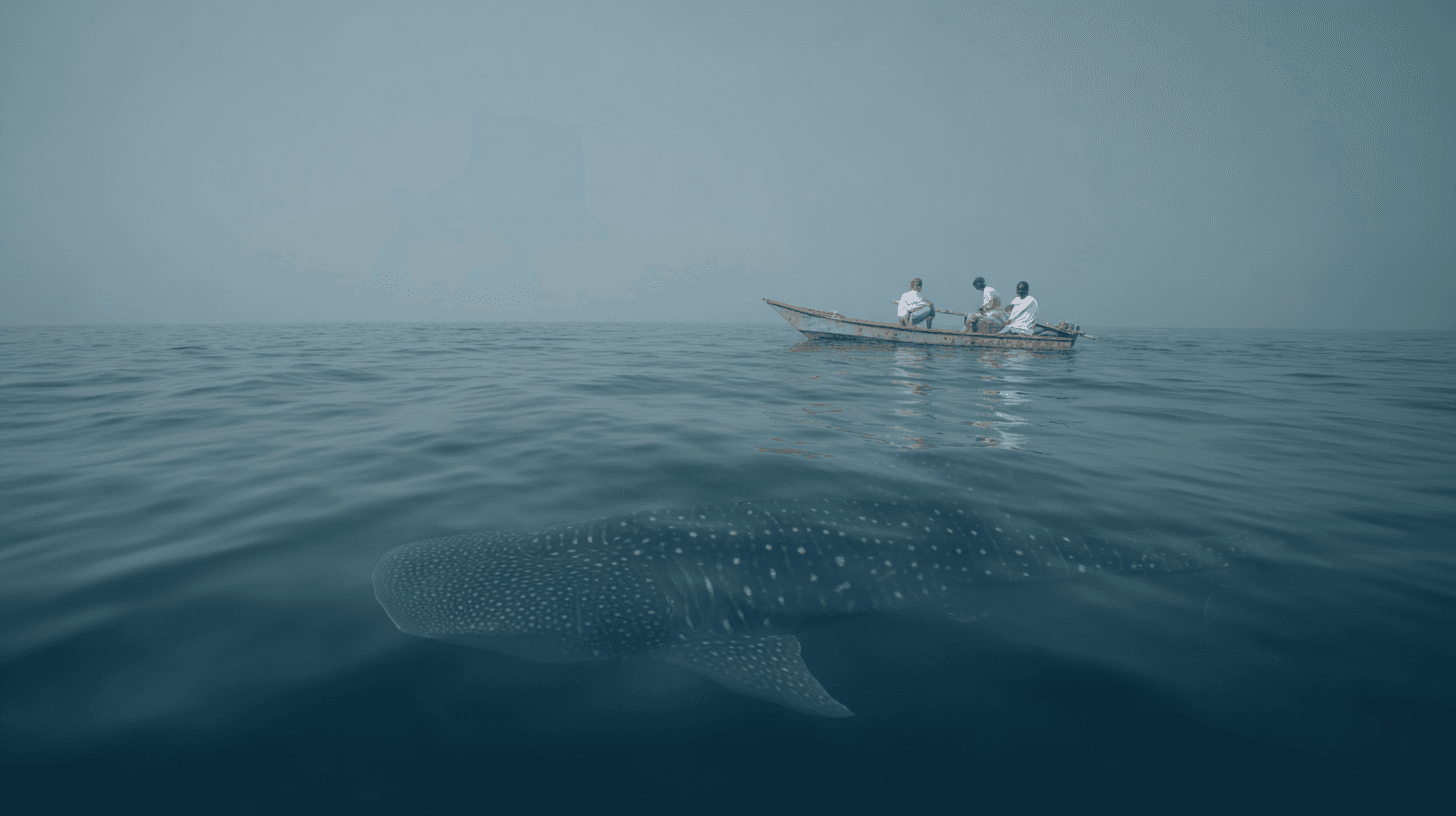

They used to hunt the biggest fish in the sea. Now they take tourists to swim with it.

The whale shark is the largest fish on earth — up to 12 meters long, weighing as much as 20 tons. Despite its size, it is harmless to humans, feeding on plankton and small fish filtered through its cavernous mouth. It moves slowly. It surfaces predictably. It is very easy to kill.

For decades, the fishermen of Donsol, a small town in the Philippines' Bicol region, hunted whale sharks. The meat was sold locally. The fins were exported to Asia. A single shark could feed a village and fund a family for months. The practice was legal, traditional, and economically essential.

By the late 1990s, the whale sharks were nearly gone.

The Discovery

In 1998, a dive operator exploring the waters off Donsol noticed something unexpected: whale sharks, and lots of them. The area's coastal waters, enriched by nutrient runoff from nearby rivers, were a seasonal gathering place for the animals. From November to June, dozens of whale sharks congregated to feed on the plankton blooms.

The fishermen already knew this. That's why they hunted there.

But the dive operator saw something different. He saw tourists. He saw an industry. He saw an alternative.

The proposal was simple: stop hunting the whale sharks and start showing them to visitors instead. A living whale shark could generate tourist revenue year after year. A dead one could only be sold once.

The fishermen were skeptical. Tourism was abstract; fishing was immediate. They knew how to hunt. They didn't know how to guide.

The Transition

The local government banned whale shark hunting in 1998, just as the tourism proposal was being developed. The timing was fortunate — the ban created pressure to find alternatives, and the tourism model provided one.

The fishermen who had hunted whale sharks became Butanding Interaction Officers — guides who take tourists out in small boats to swim alongside the animals. They use the same knowledge they always had: where the sharks feed, how they move, when they surface. The skills transferred; only the purpose changed.

By the early 2000s, Donsol was attracting tens of thousands of visitors annually. The fishermen-turned-guides were earning steady incomes. The whale sharks, no longer hunted, began returning in larger numbers.

The model became a case study in conservation economics. International organizations pointed to Donsol as proof that wildlife could be worth more alive than dead. The Philippine government replicated the approach in other areas. The story was simple and appealing: bad guys become good guys, everyone wins.

The Complications

The reality is messier. Tourism brought money but also pressure. Too many boats, too many swimmers, too much contact. Whale sharks that were harassed too often began avoiding the area. Regulations had to be developed, enforced, constantly adjusted.

Not all fishermen benefited equally. The guides who got licenses and training prospered. Others were left out. The tourism economy created new inequalities even as it reduced old pressures.

And the whale sharks themselves remained vulnerable. They migrate across international waters, moving through areas where protection is weak or absent. A shark that survives the Donsol season might be killed in Indonesian or Taiwanese waters the next month. Local conservation cannot protect a global animal.

The Persistence

Despite the complications, the Donsol model persists. The whale sharks still come. The tourists still follow. The former fishermen still guide them.

The numbers fluctuate — some years bring more sharks, some bring fewer. Climate change is shifting ocean currents and plankton distributions. What was reliable is becoming less so. But the fundamental bargain holds: protect the sharks, and the sharks will pay.

Other communities have noticed. In Mexico, the Maldives, Mozambique, and Australia, similar programs have developed. The whale shark has become a global tourism asset, its survival tied to the money it generates.

This is not conservation as charity. It is conservation as business. The morality is secondary to the economics. What matters is that the economics work.

What Remains

The old fishermen remember hunting. They remember the size of the animals, the difficulty of the kill, the way a whole village would turn out to butcher a shark. Some of them miss it. It was hard and dangerous and real in ways that guiding tourists is not.

But their children guide tourists. Their grandchildren will probably guide tourists. The knowledge of hunting is passing; the knowledge of coexistence is taking its place.

The whale sharks surface each season, mouths open, filtering the green water for plankton. The boats approach carefully, the guides watching for signs of disturbance. The tourists slip into the water and swim alongside the largest fish on earth.

It is not what it was. It is what it has become.

Sources

- Pine R. (2007). Whale Shark Tourism in Donsol Philippines

- WWF Coral Triangle Programme Reports

- Quiros A. (2007). Tourist Compliance to a Code of Conduct at Whale Shark Sites

- Araujo G. et al. (2017). Population structure of whale sharks in the Philippines