Returns

The Snow Leopard Trust

The ghost cat's guardians

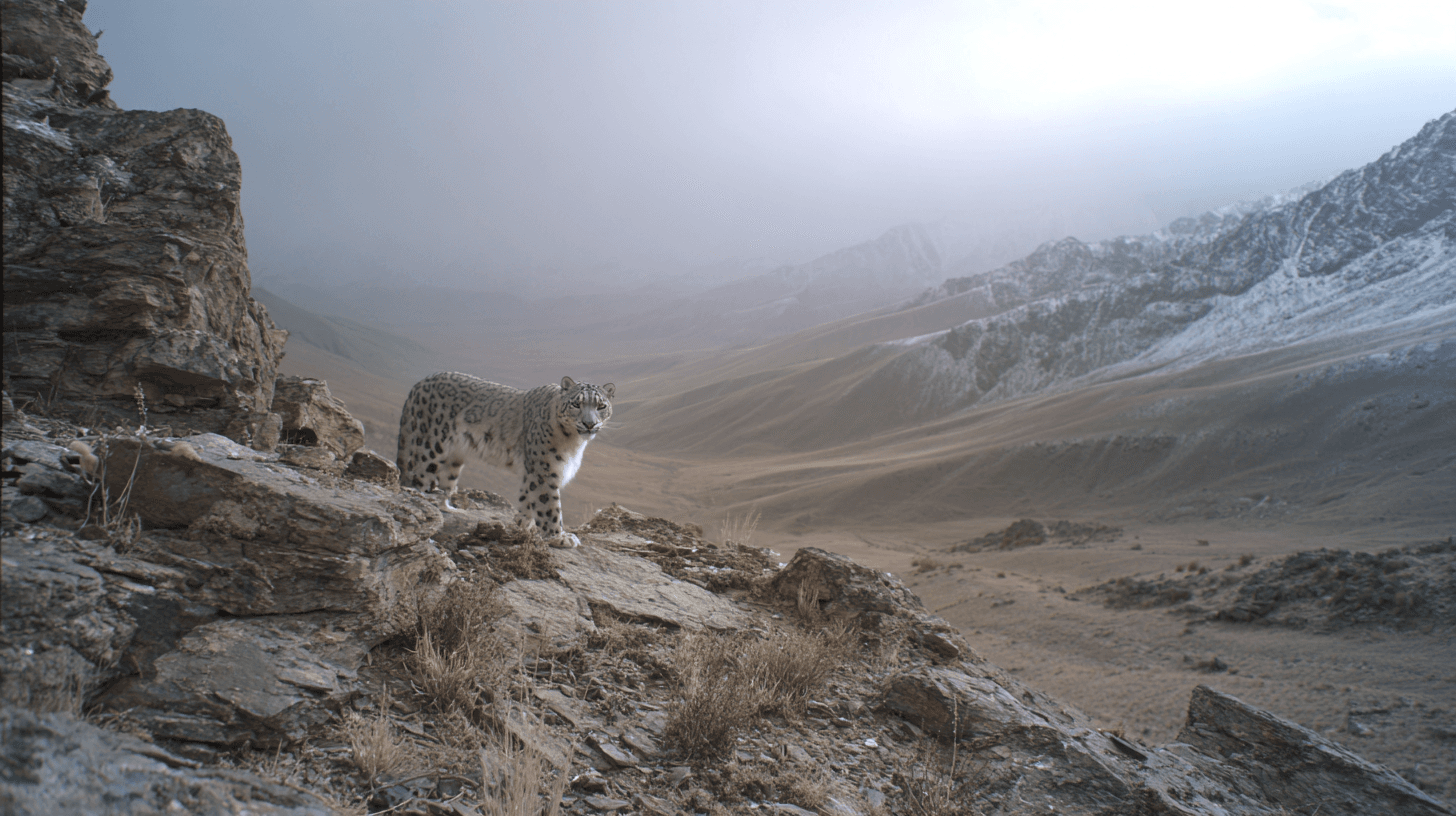

The most elusive big cat on earth survives in places where no ranger can patrol. Its protectors are the herders who once hunted it.

Snow leopards live above the tree line. Their territory is the high mountains of Central Asia — the Himalayas, the Karakoram, the Hindu Kush, the Altai, the Tian Shan. They range from 3,000 to 5,500 meters in elevation, in terrain so rugged and remote that no government can effectively manage it.

There are perhaps 4,000 to 6,500 left. No one knows exactly. Counting animals that actively avoid being seen, in landscapes that actively resist being surveyed, is more estimate than census.

What is known is that for decades, the population was declining. And in certain areas, it has stopped.

The Conflict

A snow leopard needs about 40 to 50 blue sheep or ibex per year to survive. Wild prey is hard to find. Domestic livestock is easier. A single leopard can kill a dozen sheep in a night if it gets into a corral.

For a herding family in the Karakoram, a dozen sheep might be a third of their wealth. The math is simple. Kill the leopard, or lose the sheep. For generations, herders killed leopards. The population fell.

Conservation organizations could offer only inadequate responses. Patrols were impossible — the terrain was too vast, too high, too remote. Fines were unenforceable — the same remoteness that protected the leopards protected the poachers. The only people who could actually control what happened in snow leopard territory were the people who lived there.

So that's where the solution had to come from.

The Program

In Pakistan's northern areas, the Snow Leopard Foundation began a simple program in the early 2000s. If a community agreed to protect snow leopards — no killing, no poaching, active monitoring — the foundation would insure their livestock. Kill a leopard, lose the insurance. Protect leopards, get compensated for any livestock losses.

The incentives flipped. A living leopard meant financial security. A dead leopard meant uncompensated losses.

But insurance was only part of the model. The foundation also invested in the communities themselves. Vaccination programs for livestock reduced disease losses, which were often larger than predation losses. Improved corrals made it harder for leopards to access sheep. Women's handicraft cooperatives created alternative income streams. The conservation program became a development program.

Similar models spread across snow leopard range. In Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan, India, and Nepal, variations on the same theme emerged: compensate losses, involve communities, make protection economically rational.

The Evidence

In areas with active community programs, retaliatory killings have dropped dramatically. Camera trap surveys show stable or increasing snow leopard populations. Herders who once shot leopards on sight now report sightings to researchers.

The relationship has shifted from adversary to something more complex. Herders still lose livestock. They still resent the losses. But they no longer view leopards as enemies to be eliminated. They view them as neighbors to be managed — costly, sometimes, but worth keeping around.

Some communities have gone further, developing snow leopard tourism. Photographers and wildlife enthusiasts pay significant sums for a chance to see the ghost cat. The money goes directly to villages, creating economic value from living leopards that dead ones could never provide.

The Limits

The programs work where they are implemented. They do not work everywhere. Snow leopard range covers 12 countries and nearly 2 million square kilometers. Community conservation reaches a fraction of that territory.

Climate change is pushing snow leopards higher as temperatures rise and tree lines advance. Some models suggest they could lose 30 percent of their habitat by 2070. The mountains that were their refuge may become their trap.

Meanwhile, demand for snow leopard parts persists in traditional medicine markets. Poaching for trade, rather than retaliation, remains a threat that community programs cannot fully address. A leopard skin can fetch $500 in the illegal market — more than a herder makes in months.

What Remains

The ghost cat is still there, in the high places where no one else wants to live. It hunts at dawn and dusk, moving along ridgelines and through boulder fields, visible for moments and then gone.

The herders are still there too, moving their animals between summer and winter pastures, losing the occasional sheep, coexisting with a predator that their grandparents would have killed without hesitation.

The relationship is not peaceful. It is not sentimental. It is a negotiation, constantly renewed, between species that need the same landscape for different purposes.

The leopards are not saved. They are still endangered, still precarious, still dependent on decisions made by people who have every right to make different decisions. But they are not disappearing as fast as they were. And in conservation, that counts as progress.

Sources

- Jackson R. and Hunter D. (1996). Snow Leopard Survey and Conservation Handbook

- Snow Leopard Trust Annual Reports 2018-2024

- Mishra C. et al. (2003). The Role of Incentive Programs in Conserving the Snow Leopard

- Johansson O. et al. (2016). Land sharing is essential for snow leopard conservation