Essays

The Pearl Divers

Before the oil

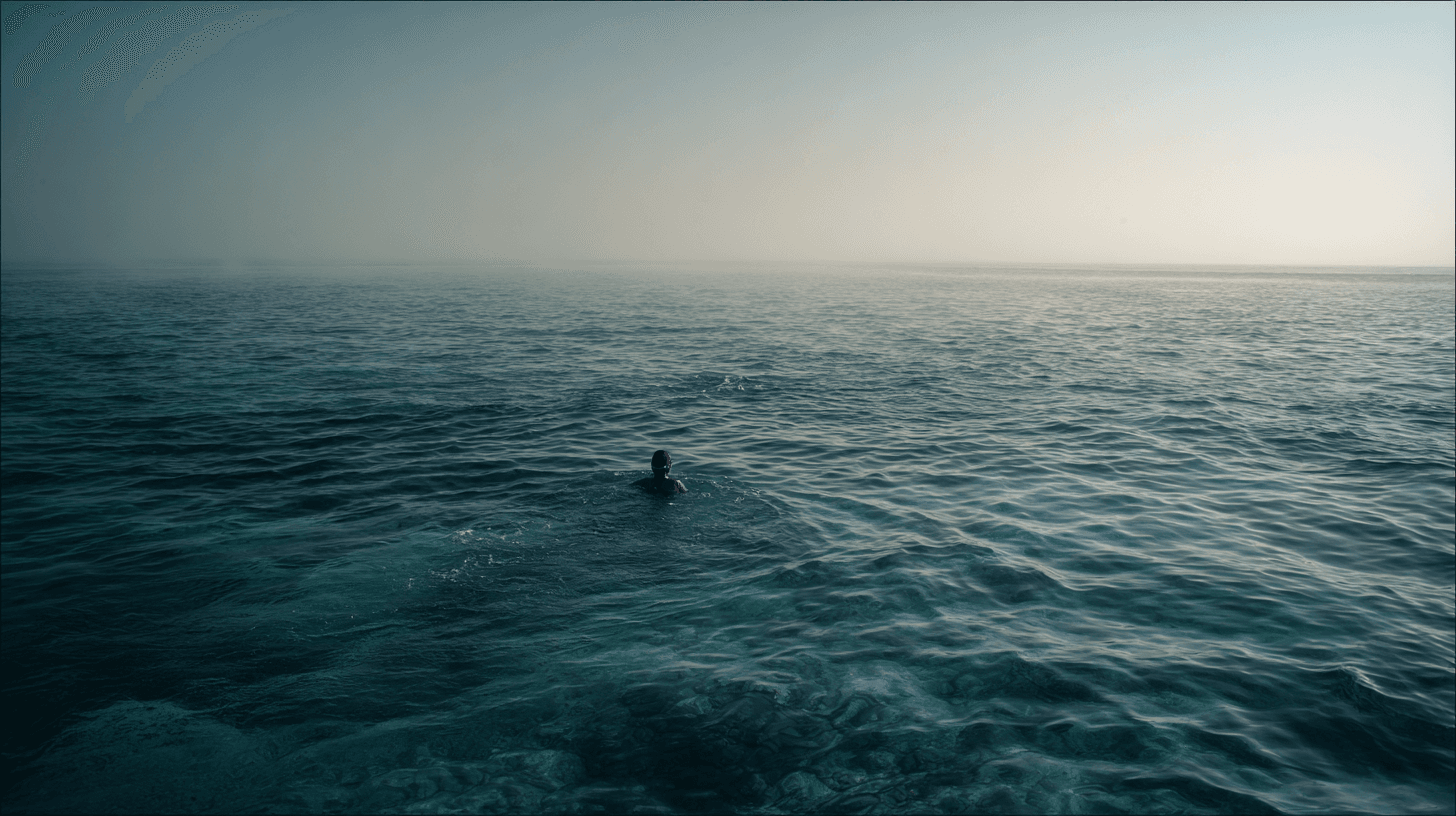

Before oil, there were pearls.

The Gulf states — Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the Emirates — built their economies on nacre. Divers descended 15-40 meters on a single breath, harvesting oysters from the seabed. The work was brutal, the mortality high, the pearls worth fortunes.

Then Japanese cultured pearls crashed the market in the 1930s. Then oil was discovered. The industry collapsed within a generation.

The Physiology

Pearl divers developed measurable physical adaptations. Studies of traditional diving populations show enlarged spleens — the organ that stores oxygenated red blood cells. Under diving stress, the spleen contracts, releasing oxygen reserves.

This is the "diving reflex" pushed to extremes. Heart rate drops. Blood vessels constrict. The body rations oxygen for brain and heart.

Experienced divers could stay underwater for two to three minutes. Some claimed longer. The claims may be exaggerated. The physiology is not.

The Economics

A single exceptional pearl could be worth more than a year's wages. Most dives produced nothing valuable. The economics were lottery-like — long odds, occasional jackpots.

Divers were often indebted to boat captains. The debt system kept them diving even when the work was killing them. An estimated 50% of divers developed hearing damage from pressure. Many died.

The pearls financed the merchant families who still dominate Gulf business. The divers are mostly forgotten.

The Collapse

Mikimoto's cultured pearls, perfected in the 1920s, produced gems indistinguishable from natural ones at a fraction of the cost. By the 1930s, Gulf pearl prices had crashed 90%.

Oil was discovered in Bahrain in 1932. The timing was fortunate. The Gulf economies pivoted from pearls to petroleum without pausing. The divers became irrelevant.

The Memory

Bahrain and the UAE have built pearl diving museums. Heritage festivals recreate the dives. The boat songs are performed. The nostalgia is carefully curated.

What's remembered: the romance, the heritage, the connection to the sea.

What's less remembered: the debt bondage, the deaths, the industry that depended on disposable labor.

The Physiology Again

The enlarged spleens don't persist without the diving. Within a generation of stopping, the adaptation fades. The bodies that made the industry possible are gone.

But the research continues. Free diving athletes train with traditional breath-hold divers from Indonesia, Japan, Korea. The knowledge of how to push human physiology underwater didn't disappear — it moved to different contexts.

The Question

The pearl diving industry was exploitative and dangerous. Its collapse saved lives. The oil that replaced it transformed a region.

What's worth preserving from this history? Not the industry itself. Maybe the physiological knowledge. Maybe the boat songs. Maybe just the memory that these cities were built on something other than petroleum.

The pearl beds still exist. Oysters still grow there. No one dives for them anymore.

Sources

- Al-Hijji Y. (2010). Kuwait and the Sea

- Carter R. (2005). The History and Prehistory of Pearling in the Persian Gulf

- Villiers A. (1948). Sons of Sinbad

- Heard-Bey F. (1982). From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates