Systems

The Honey Guides

The partnership that predates language

A bird calls. A human follows. They find honey together. They have been doing this for 100,000 years.

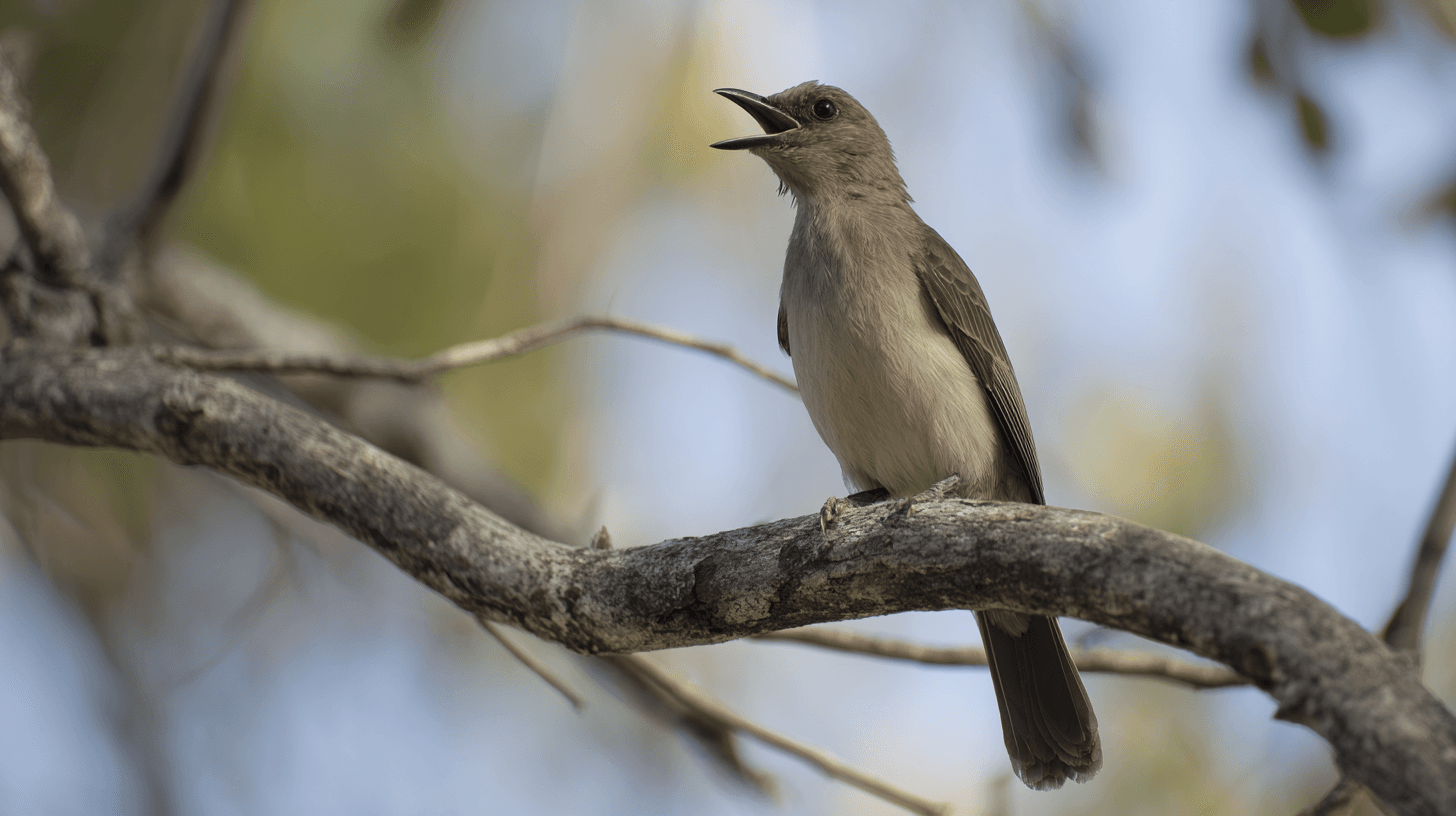

The greater honeyguide is a small, nondescript bird. Brown. Streaked. Easy to miss. But if you know how to listen, it will lead you to something you cannot find alone.

Beehives in the African bush are hidden — in hollow trees, rock crevices, termite mounds. A human can walk past a hundred hives without seeing any. The honeyguide sees them all. It watches bees. It follows their flight paths. It knows where the honey is.

But the honeyguide cannot open a hive. Its beak is too small. It cannot smoke out the bees or break through the wood. What it can do is find a partner who can.

The bird makes a distinctive call — a repetitive chattering that carries through the bush. A human hears it and follows. The bird moves from tree to tree, calling, waiting, leading. Eventually it stops, perches near a hidden hive, and falls silent. The human opens the hive, takes the honey, and leaves behind the wax and larvae. The bird eats what remains.

Both get what they could not get alone.

The Science

In 2016, researchers in Mozambique published a study that stunned evolutionary biologists. They demonstrated that the partnership was not one-sided — the birds actively responded to human signals.

The Yao people of the Niassa region use a specific call to summon honeyguides: a loud trill followed by a grunt, "brrr-hm." When researchers played recordings of this call, honeyguides were significantly more likely to approach and initiate guiding behavior. Random human sounds did not work. The birds recognized the call.

This meant the partnership was genuinely reciprocal. The birds were not just leading humans who happened to follow. They were responding to a signal, entering into an agreement. The call meant: I am ready. Show me.

More remarkably, the call varies by region. The Hadza people of Tanzania use a different sound — a melodic whistle. The honeyguides there respond to that sound, not the Mozambican one. The birds have learned the local language.

The Age

How old is this partnership? Archaeological evidence suggests modern humans have harvested honey in Africa for at least 100,000 years. Rock art depicting honey hunting dates back 20,000 years. The partnership may be as old as humanity itself — older than language, older than agriculture, older than dogs.

The honeyguide is the only wild animal that actively seeks human cooperation to obtain food. Other animals tolerate humans, exploit humans, follow humans. The honeyguide recruits humans.

This required both species to change. The birds had to learn to recognize humans as useful, to approach rather than flee, to develop and respond to signals. The humans had to learn to recognize the bird's behavior, to trust it, to share the reward. Both had to teach their offspring.

The result is not domestication. The birds are wild. They do not breed in captivity. They cannot be kept. But they have incorporated humans into their survival strategy — and humans have incorporated them.

The Decline

The partnership is fading. Not because the birds have changed, but because the humans have.

In many areas, traditional honey hunting is disappearing. Young people move to cities. Sugar becomes cheap. The knowledge of how to call the birds, how to follow them, how to reward them, passes to fewer and fewer practitioners.

When humans stop hunting honey, the birds stop guiding. Researchers have documented this in areas where the tradition has been lost. The birds still exist. They still know where the hives are. But they no longer approach humans. They have unlearned the partnership.

This can happen within a single generation. A bird that was never rewarded by a human does not teach its offspring to seek humans. The chain breaks.

The Persistence

In some regions, the partnership remains strong. The Yao of Mozambique still hunt honey traditionally. The Hadza of Tanzania still follow the guides. The Boran people of Kenya still whistle for the birds that their ancestors whistled for.

These are not re-enactments for tourists. They are living traditions, maintained because they work. A good honeyguide can increase a honey hunter's success rate by a factor of three or more. The birds are worth following.

What persists is not just a technique but a relationship — one built over thousands of generations, one that requires both parties to participate, one that cannot be imposed from above or revived by policy.

What Remains

The honeyguide still calls. In the places where someone still answers, the partnership continues. The bird finds the hive. The human opens it. Both eat. And somewhere, a young bird watches, learning that the strange two-legged creatures are worth approaching.

It is the oldest collaboration on earth. It requires nothing but attention, reciprocity, and the willingness to follow a small brown bird into the bush.

That, and someone who still knows the call.

Sources

- Spottiswoode C. et al. (2016). Reciprocal signaling in honeyguide-human mutualism

- Isack H. & Reyer H. (1989). Honeyguides and honey gatherers: Interspecific communication in a symbiotic relationship

- Crittenden A. (2011). The importance of honey consumption in human evolution

- Wood B. et al. (2014). Mutualism and manipulation in Hadza-honeyguide interactions