Conservation

The Gorilla Doctors

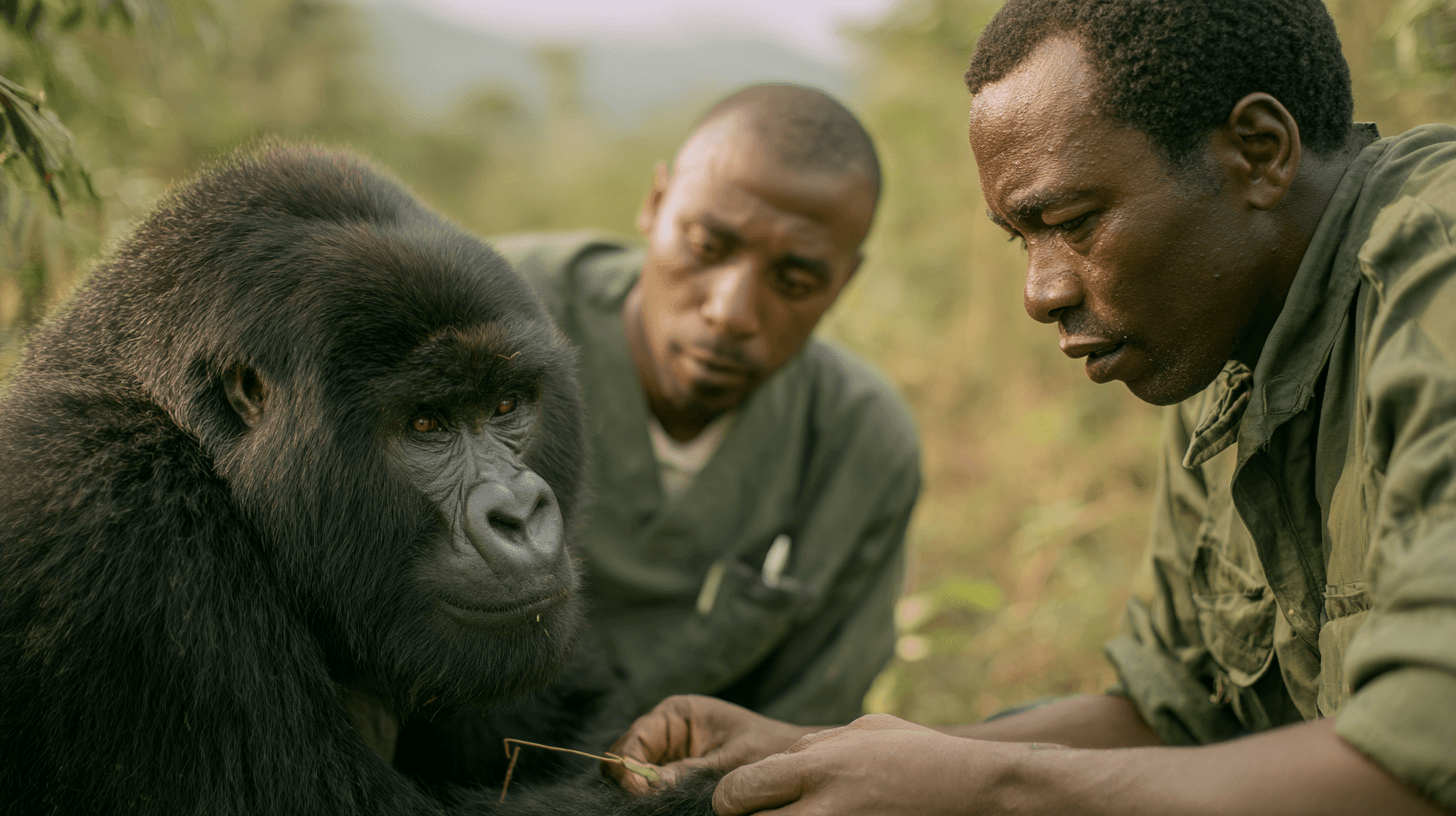

The veterinarians who make house calls in the forest

The mountain gorilla cannot be captive-bred.

Cannot be relocated. Cannot survive in a zoo. The species exists only in two small patches of forest — the Virunga Mountains where Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo meet, and Bwindi Impenetrable Forest in Uganda. About 1,000 animals total. If they die there, they die everywhere.

So the doctors go to them.

Gorilla Doctors is the only organization in the world that provides veterinary care to wild great apes. Their patients cannot be brought to a clinic. Their patients live in montane forest at 3,000 meters, in terrain so steep that a house call means hours of climbing through bamboo and stinging nettles. Their patients weigh 200 kilograms and can tear a human apart.

The vets go anyway.

The organization started in 1986, when the mountain gorilla population had crashed to around 250 animals. Dian Fossey had been murdered the year before. Rwanda was sliding toward genocide. The gorillas were dying from poaching, habitat loss, and diseases caught from the humans who surrounded them.

A single vet began making rounds. When a gorilla was reported injured or sick, he would trek into the forest, assess the situation, and intervene if necessary. Snare removals were common — wire traps set for antelope that caught gorilla hands instead. Respiratory infections required darting and treatment. Wounds from fights needed cleaning and antibiotics.

The work was controversial. Wild animals are supposed to stay wild. Intervention risks habituating them to humans, disrupting social structures, creating dependency. Every conservation textbook says to leave wildlife alone.

But the mountain gorilla isn't ordinary wildlife. The population is so small that every individual matters. A silverback killed by infection might take his whole group with him — females scattering, infants dying, years of social bonds destroyed. The genetic pool is so limited that every breeding adult counts. The math demands intervention.

Today Gorilla Doctors employs a team of veterinarians across all three countries. They monitor every habituated gorilla group — tracking health, watching for injuries, responding when something goes wrong. Their protocols are precise: intervene only when necessary, treat as quickly as possible, minimize contact time. They've removed hundreds of snares, treated dozens of respiratory infections, performed emergency surgeries in the field.

The results are measurable. Infant mortality has dropped by half since regular veterinary care began. The population is growing for the first time in decades. Mountain gorillas are the only great ape whose numbers are increasing.

The irony is sharp. The tourists who pay $1,500 for an hour with gorillas sometimes transmit the respiratory infections that the doctors then treat. Human-to-gorilla disease transmission is the leading health threat to the population. The same visitors who fund conservation also endanger it.

But the system self-corrects. Tourism revenue pays for the veterinary teams. Tourism revenue pays for rangers who protect against poaching. Tourism revenue funds community programs that give local people a stake in gorilla survival. The money that brings disease also brings the cure.

The doctors have learned to work within the paradox. They've developed protocols for tourist visits — distance requirements, mask mandates, time limits. They've trained local staff to recognize symptoms and report quickly. They've built a surveillance system that catches outbreaks before they spread.

When COVID arrived, the gorillas were isolated entirely. Tourism stopped. The revenue collapsed. But the doctors kept working — now monitoring for a disease that could devastate the population if it crossed from human to ape. The tourists who might have spread it were gone. The doctors who might have to treat it remained.

The mountain gorilla exists because people decided it should exist. Not natural selection, not wilderness, not the invisible hand of evolution — but deliberate intervention, funded by tourism, delivered by veterinarians who climb mountains to treat animals that cannot come to them.

The species is a product of human choice. The doctors make sure it stays that way.

Sources

- Gorilla Doctors annual reports; Rwanda Development Board tourism statistics; Virunga Massif population surveys; International Gorilla Conservation Programme