Systems

The Frankincense Road

The scent that built empires

The knife cuts the bark. Milky sap bleeds from the wound, exposed to the desert air. Over days it hardens into translucent tears — amber, gold, precious beyond measure.

For three thousand years, frankincense resin from the Dhofar coast of Arabia was worth more than gold.

The Egyptians used it to embalm pharaohs. The Romans burned it in temples and paid in silver. The Christians brought it to Bethlehem. The trade routes that carried it across Arabia and into the Mediterranean built cities, funded armies, and shaped the geography of power for two millennia.

The trees are still there. The harvesters still climb them. The scent is the same.

The Harvest

Frankincense is harvested the same way it was harvested 3,000 years ago. In spring, workers make shallow cuts in the bark of the Boswellia tree. White sap bleeds from the wounds, hardens in the dry air, and forms the tears that are collected two weeks later. The process is repeated three to four times per season. A single tree might yield 10 kilograms of resin per year.

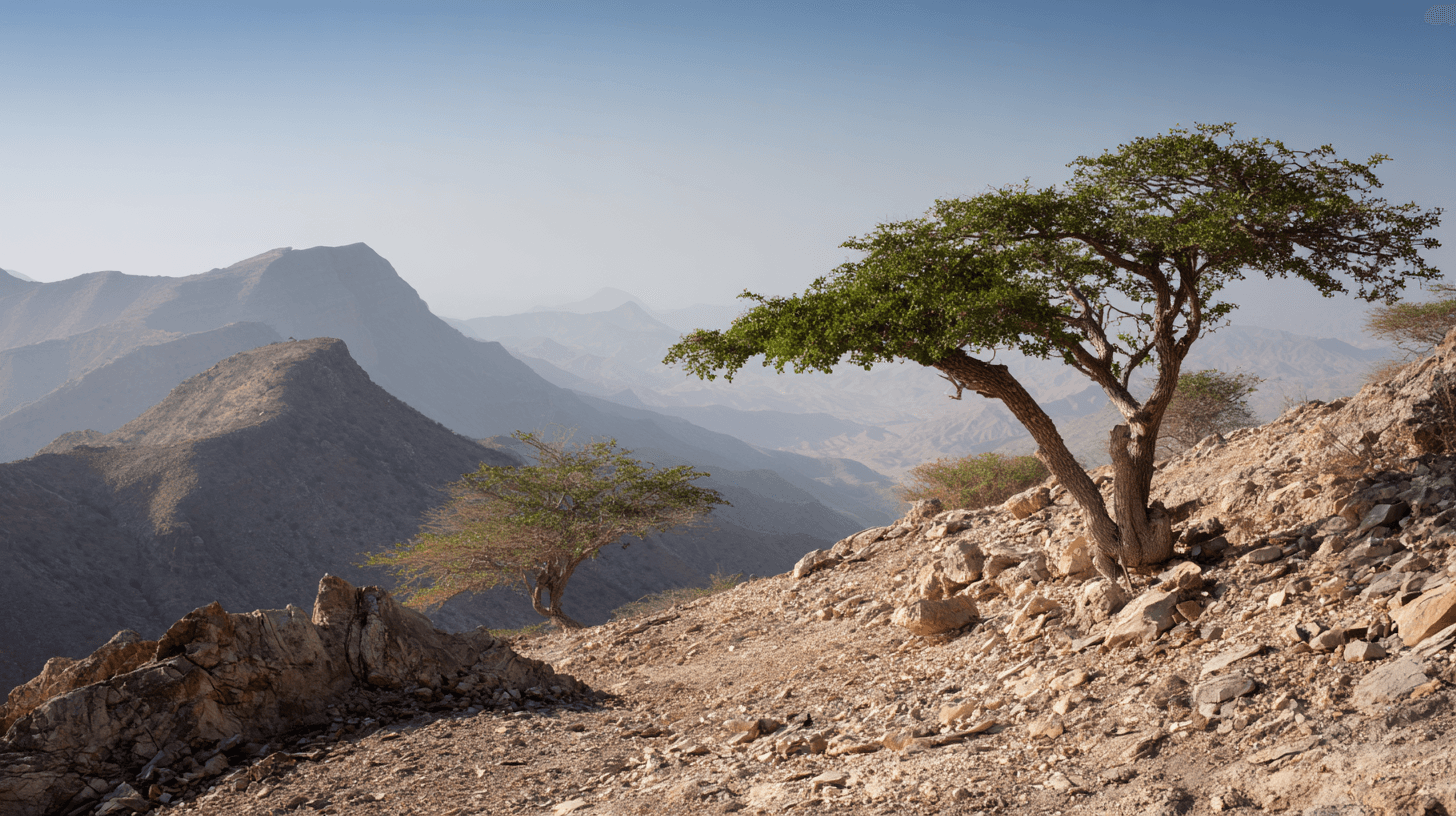

The quality depends on everything: the tree's age, the timing of the cut, the weather during the bleeding period, the skill of the harvester. The finest resin — pale, translucent, called hojari in Oman — comes from old trees on rocky slopes where the roots must work hard. Stress makes better sap.

The families who harvest frankincense have done so for generations. The trees are inherited, the techniques passed down, the best groves jealously guarded. It is not industrial agriculture. It is something closer to viticulture — a craft where knowledge accumulates over centuries and quality cannot be rushed.

The Trade

At its peak, the frankincense trade was one of the most valuable in the ancient world. Camel caravans carried the resin north through Arabia, west into Egypt, east to Persia and India. The journey from Dhofar to Gaza took about two months and crossed some of the harshest terrain on earth.

The cities that controlled the trade became wealthy beyond proportion to their size. Petra carved its facades into rose-red cliffs with frankincense money. Shibam built its mud-brick towers with frankincense money. The Queen of Sheba — whose legendary kingdom lay somewhere in Yemen or Ethiopia — was almost certainly a frankincense queen.

The Romans spent so much on incense that Pliny the Elder complained it was draining the empire's silver reserves. The Emperor Nero reportedly burned a year's supply of frankincense at his wife's funeral — an extravagance that contemporaries found shocking even by imperial standards.

The Decline

The trade collapsed twice. First, when Christianity replaced Roman paganism and the temples stopped burning incense. Second, when sea routes replaced land routes and the camel caravans became obsolete.

By the 19th century, frankincense was a regional curiosity, used in local traditions and religious ceremonies but no longer a commodity that built cities. The harvesters continued their work, but the global market had moved on.

The trees, however, remained. The Dhofar coast still produces some of the finest frankincense on earth. The families who work the groves still know how to harvest it. The knowledge survived even when the market did not.

The Return

In recent decades, frankincense has found new markets. Aromatherapy, natural medicine, luxury perfumery — all have discovered or rediscovered the resin. High-quality Omani frankincense now sells for $50 or more per kilogram, a price that makes sustainable harvesting economically viable.

The Omani government has invested in the industry, establishing protected areas, supporting cooperatives, and promoting frankincense as part of the country's cultural heritage. The ancient trade routes are now UNESCO World Heritage sites. The trees that once funded empires now fund conservation programs.

But there are concerns. Climate change is stressing the trees — the monsoon rains that the Boswellia depends on are becoming less predictable. Overharvesting in some areas has weakened tree populations. A fungal disease is spreading through groves in Ethiopia and Somalia. The same trees that survived three millennia of commerce may not survive the next century of environmental change.

What Remains

The frankincense still bleeds from the cuts in the bark. The tears still harden in the desert air. The scent, when burned, is still the same scent that filled Egyptian tombs and Roman temples and the churches of Byzantium.

Whether the trees will still be producing in another hundred years is not certain. The climate is shifting. The groves are stressed. The knowledge of harvesting, while still intact, depends on there being something to harvest.

But for now, the trade continues. The caravans are gone, replaced by trucks and cargo ships. The temples are gone, replaced by yoga studios and perfume boutiques. The trees remain, doing what they have done for longer than any human institution has existed: bleeding sap, healing wounds, surviving.

Sources

- Peacock D. and Blue L. (2007). The Ancient Red Sea Port of Adulis

- Van Beek G. (1960). Frankincense and Myrrh in Ancient South Arabia

- Farah A. (1994). The Milk of the Boswellia Forests

- Bongers F. et al. (2019). Frankincense in peril