Systems

The Desert Runners

The messengers who outran horses

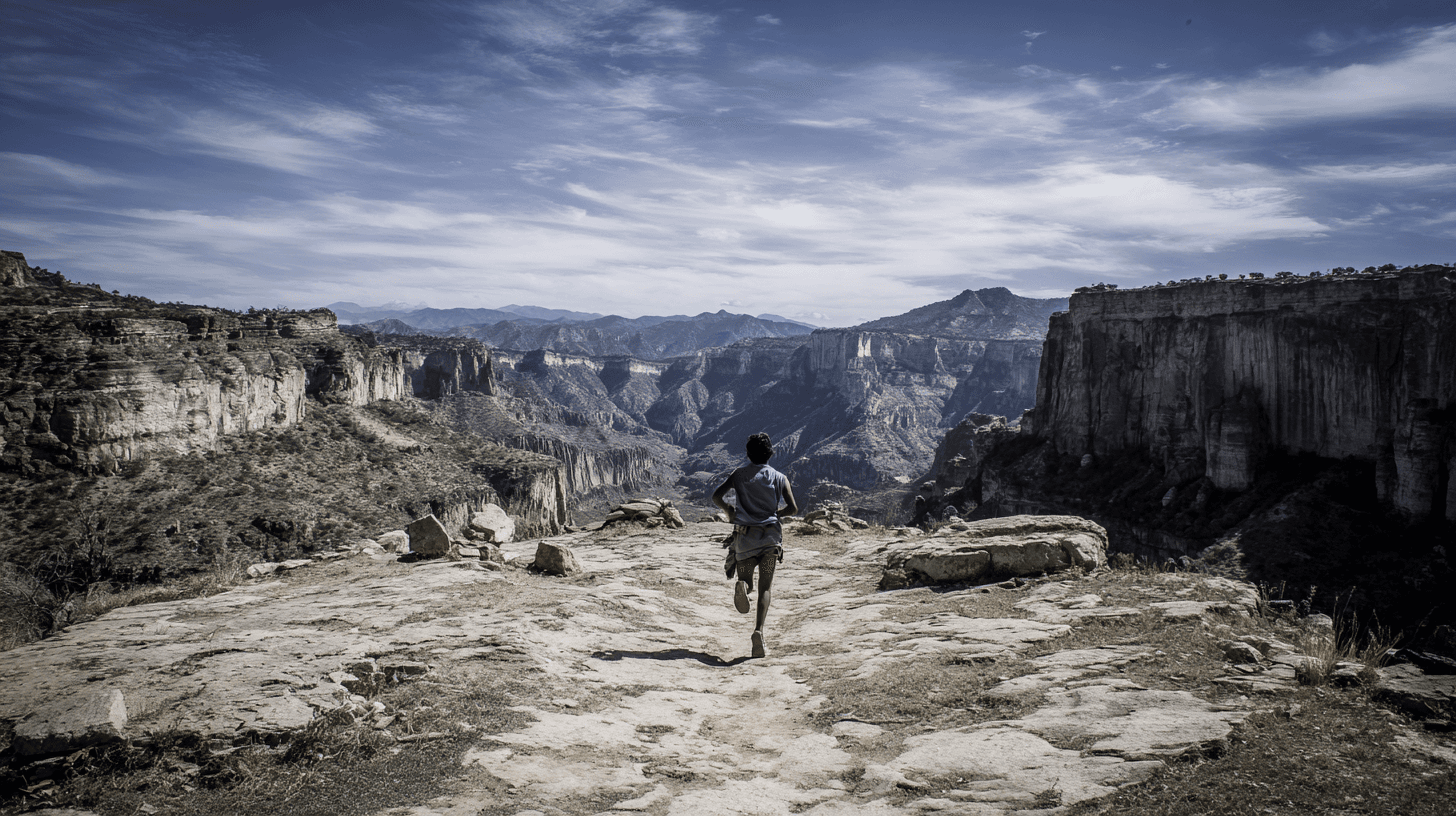

The Rarámuri people of northern Mexico can run hundreds of kilometers through mountain canyons. Their endurance may hold clues to human evolution.

The Rarámuri — called Tarahumara by outsiders — live in the Copper Canyon region of Chihuahua, a landscape of deep gorges and high plateaus in the Sierra Madre. Their name means "runners" or "those who run fast," and they have earned it. For centuries, they have practiced long-distance running as transportation, sport, and cultural identity.

Their abilities attracted scientific attention in the late 20th century. Runners who could cover 200 kilometers in mountain terrain without apparent strain seemed to violate everything known about human physiology. The Rarámuri were not professional athletes. They were farmers, ranchers, subsistence workers — people who ran extraordinary distances as part of ordinary life.

The research that followed changed how scientists understand human endurance. The Rarámuri may not be superhuman. They may simply be doing what humans evolved to do.

The Running

Rarámuri running is not like Western running. The pace is slow, steady, sustainable over enormous distances. The footwear is minimal — traditionally huaraches, sandals with leather straps and soles of tire rubber or plant fiber. The form is light, with short strides and feet landing beneath the body rather than ahead of it.

The distances are remarkable. Traditional rarajípari games involve teams kicking a wooden ball through canyon trails for 100 kilometers or more, running continuously through the night. Individual runners have been documented covering 300 kilometers in less than 48 hours. Elite Rarámuri runners have won ultramarathons against international competition, often while wearing sandals and traditional clothing.

The running is social. Races are community events, accompanied by betting, drinking, and celebration. Children run with adults. Older runners continue into their 60s and beyond. The activity is not specialized or competitive in the Western sense — it is simply what Rarámuri do, part of the fabric of life.

The culture supports the practice. Running is valued, trained, and rewarded. Children grow up running. The terrain — endless trails through mountains and canyons — provides natural training ground. The environment and the culture together produce runners that other populations cannot match.

The Science

Scientists who studied the Rarámuri were trying to understand a paradox. Modern athletes, with all their training and technology, cannot match the endurance of barefoot farmers. Why?

The answer involves the human body's design. Humans are persistence hunters — we evolved to run prey to exhaustion over long distances. We cannot outrun a deer in a sprint, but we can outrun it over hours, tracking it as it tires, running until it collapses. This strategy requires endurance that no other primate possesses.

The adaptations are numerous. We sweat, allowing continuous cooling during exertion. Our tendons store and release energy efficiently. Our breathing is decoupled from our stride, allowing us to regulate oxygen independently of movement. Our brains are wired for long-distance travel, for tracking, for the persistence that hunting requires.

The Rarámuri have not evolved special abilities. They have simply maintained the abilities that all humans once had. Modern populations have lost them — to shoes that alter gait, to sedentary lifestyles that reduce endurance, to cultures that do not value running. The Rarámuri preserved what others discarded.

The Footwear

The huaraches became famous. The minimal sandals, offering protection without constraining movement, seemed to produce better running form than modern athletic shoes. The scientific debate about footwear transformed into a commercial trend. "Barefoot" running shoes proliferated.

The relationship was more complex than the marketing suggested. The Rarámuri develop their running form over lifetimes, beginning in childhood. Their feet adapt, their tendons strengthen, their proprioception refines. An adult switching to minimal footwear does not instantly gain these adaptations. Many who tried were injured.

The Rarámuri themselves have been affected by the attention. Some runners have been recruited to compete in international events. Commercial interests have sought to partner with the community. The traditional practice has been pulled into global markets that value it for different reasons than the Rarámuri do.

The Threat

The Rarámuri way of life is under pressure. Their lands are targeted by drug cartels and illegal loggers. Climate change is altering the canyons where they run. The younger generation faces the same pulls toward modernity that affect indigenous communities everywhere.

The running persists but is changing. Traditional races continue, but participation fluctuates. Elite runners compete internationally but are not always welcomed back with the prizes they deserve. The practice that defined the community for centuries faces an uncertain future.

Some efforts aim to preserve the tradition. Running events organized by Rarámuri draw participants from around the world. Documentary filmmakers and journalists spread awareness. The community itself maintains its practices as best it can, adapting to conditions that shift faster than tradition can accommodate.

What Remains

The runners remain. In the canyons of the Sierra Madre, Rarámuri still run distances that seem impossible, still kick balls through mountain trails, still move through the landscape as they have for centuries. The tradition is diminished but not dead.

The knowledge remains too — held in bodies trained from childhood, in communities that value endurance, in the example of what humans can do when they do what they evolved to do. The Rarámuri are not freaks. They are humans, showing other humans what is possible.

The science continues. Researchers still study Rarámuri running, still learn from what they observe, still revise understanding of human physiology. The runners are subjects, but they are also teachers. What they know, what they do, what they are — this is data that no laboratory can generate.

The canyons remain. The trails remain. The tradition remains, adapted and challenged and still alive. The runners who outran horses continue to run, at their own pace, on their own terms, doing what their ancestors did and their descendants may or may not do.

Humans were born to run. The Rarámuri remember how.

Sources

- Lieberman D. et al. (2010). Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners

- McDougall C. (2009). Born to Run

- Lumholtz C. (1902). Unknown Mexico

- Nabokov P. (1981). Indian Running