Systems

The Conservancy Model

When the ranchers became landlords

The cattle ranches were failing.

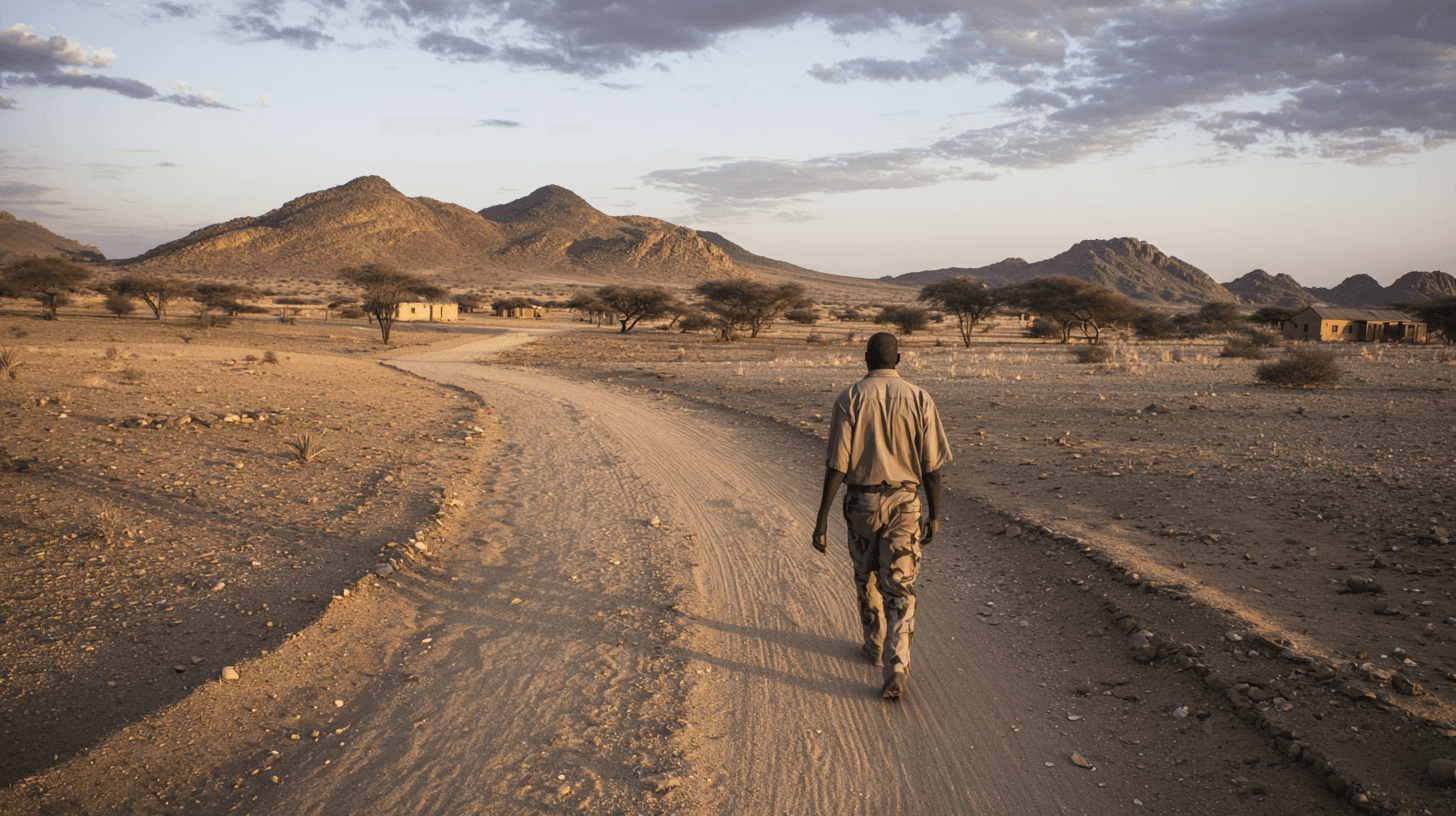

Drought came more often. Lions took more calves. Beef prices fell while costs rose. The families who had displaced the wildlife were being displaced themselves — selling off land, moving to Nairobi, watching generations of work collapse.

Then someone suggested renting the land to lions instead.

The idea was simple. A ranch that loses money running cattle might make money running wildlife. Safari operators need land. Wildlife needs space. Landowners need income. Connect the three, and everyone survives.

The first conservancies emerged in Laikipia, the plateau north of Mount Kenya where white settlers had carved out ranches in the colonial era. By the 1990s, many were failing. The land was overgrazed. The wildlife had been shot out or pushed to the margins. The business model — beef for export — no longer worked.

Ol Pejeta was one of the first to convert. The ranch stopped running cattle commercially and started running rhinos. Black rhinos, critically endangered, needed protected space. Ol Pejeta had space. Conservation fees from safari lodges replaced beef revenue. The same fences that had kept wildlife out now kept poachers away.

The wildlife returned. Not just rhinos — elephants, lions, leopards, the whole suite of plains game that had been pushed out over decades. The ranch became a conservancy. The conservancy became a model.

Then the Maasai noticed.

South of Laikipia, in the rangelands around the Maasai Mara, community land was being subdivided and overgrazed. Young men killed lions to prove their courage and protect their cattle. Elephants raided crops and were speared in return. The wildlife that drew tourists to the Mara was disappearing from the community lands that surrounded it.

The conservancy model offered an alternative. Instead of subdividing land into plots too small to support cattle or wildlife, communities could lease their land collectively to safari operators. The operators built lodges. The lodges brought tourists. The tourists paid fees that went directly to landowners — every family receiving monthly payments for keeping their land open to wildlife.

The economics transformed behavior overnight.

A lion that had been a threat became an asset. Kill it, and you lose the tourists who came to see it. Protect it, and you receive payments that exceed what cattle could ever provide. The same calculation applied to elephants, to leopards, to the grasslands themselves. Suddenly conservation paid better than destruction.

The Mara Conservancies now cover over 100,000 acres of community land. Thirteen separate conservancies, each governed by local landowners, each hosting safari camps that pay lease fees and employ local staff. Poaching has dropped to near zero — the same young men who might have sold ivory now earn salaries to report poachers. Lion populations have stabilized. Elephant herds move freely across lands that once would have killed them.

The model isn't perfect. Lease payments fluctuate with tourism. Droughts still stress the system. Land disputes simmer. And the fundamental question remains: what happens when the tourists stop coming?

COVID provided a test. When safari lodges closed in 2020, conservancy payments collapsed. Some landowners talked about returning to cattle, to subdivision, to the old ways. But most held on. The wildlife was worth more alive than dead, even in a bad year. The calculation had changed permanently.

Today the conservancy model is spreading across East Africa. Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe — anywhere community land borders protected areas, the same logic applies. Tourism creates value. Value creates incentives. Incentives change behavior.

The ranchers who couldn't make money from cattle now make money from lions. The lions that were being poisoned now generate income. The land that was being destroyed now funds schools and clinics and water projects.

The math finally works. The wildlife gets to stay.

Sources

- Conservancy management data; Kenya Wildlife Conservancies Association; Ol Pejeta Conservancy annual reports; Maasai Mara Wildlife Conservancies Association